The previous tutorial introduced object-oriented concepts. Now you’ll put them into practice. By the end of this tutorial, you’ll create your own classes, define fields and methods, and instantiate objects.

Creating a Class

A class definition starts with the class keyword followed by the class name. By convention, class names start with an uppercase letter and use PascalCase.

public class Car {

// Fields and methods go here

}Save this in a file named Car.java. The filename must match the class name exactly.

Adding Fields

Fields store the data an object holds. Declare them inside the class but outside any method.

public class Car {

String make;

String model;

int year;

double mileage;

}Each Car object will have its own make, model, year, and mileage. These fields define what a Car knows about itself.

Adding Methods

Methods define what an object can do. They have access to the object’s fields.

public class Car {

String make;

String model;

int year;

double mileage;

void displayInfo() {

System.out.println(year + " " + make + " " + model);

System.out.println("Mileage: " + mileage);

}

void drive(double miles) {

mileage += miles;

System.out.println("Drove " + miles + " miles");

}

}The displayInfo() method prints the car’s details. The drive() method adds miles to the odometer. Both methods work with the object’s own data.

Creating Objects

Use the new keyword to create an object from a class.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Car myCar = new Car();

}

}This creates a Car object and stores a reference to it in the variable myCar. The object exists in memory. The variable holds its address.

Accessing Fields and Methods

Use the dot operator to access an object’s fields and methods.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Car myCar = new Car();

// Set field values

myCar.make = "Toyota";

myCar.model = "Camry";

myCar.year = 2022;

myCar.mileage = 15000;

// Call methods

myCar.displayInfo();

myCar.drive(50);

myCar.displayInfo();

}

}Output:

2022 Toyota Camry

Mileage: 15000.0

Drove 50.0 miles

2022 Toyota Camry

Mileage: 15050.0Multiple Objects

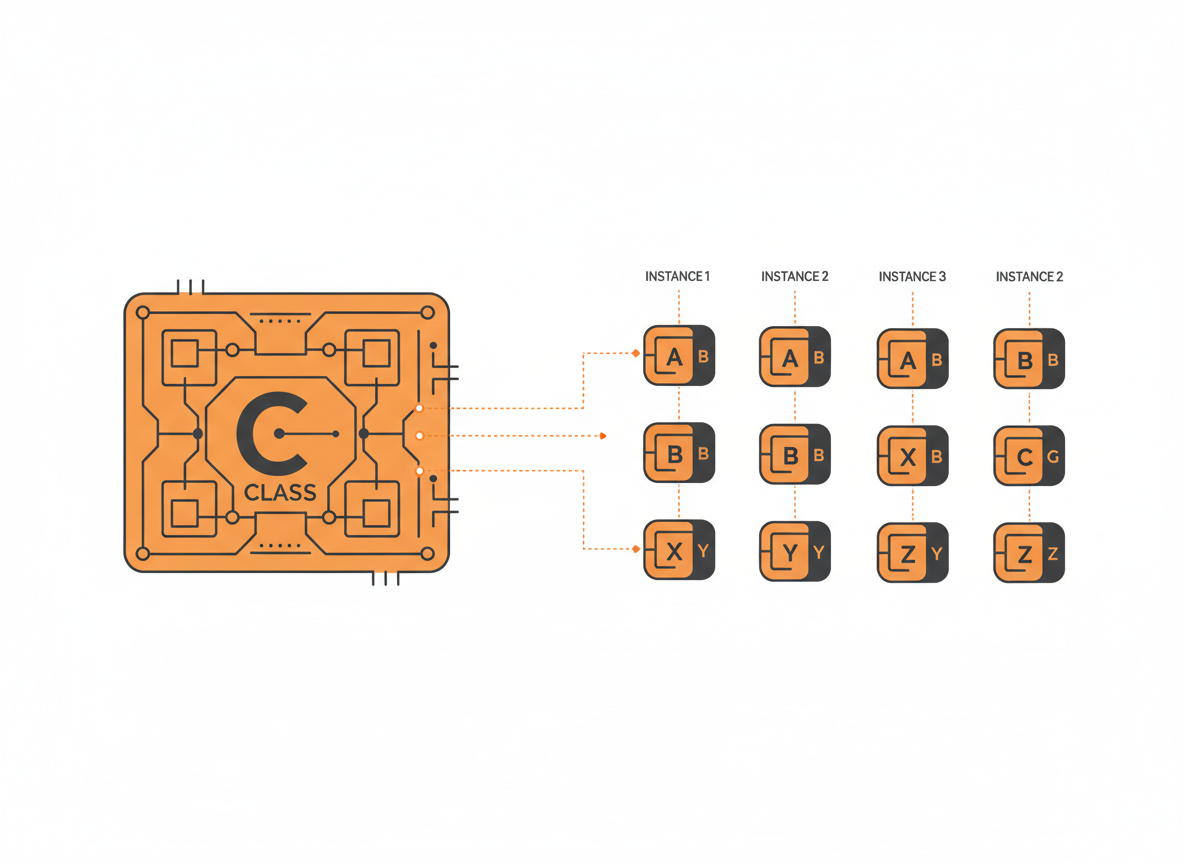

One class can produce many objects. Each maintains its own field values.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Car car1 = new Car();

car1.make = "Toyota";

car1.model = "Camry";

car1.year = 2022;

car1.mileage = 15000;

Car car2 = new Car();

car2.make = "Honda";

car2.model = "Civic";

car2.year = 2021;

car2.mileage = 28000;

car1.displayInfo();

System.out.println();

car2.displayInfo();

}

}Output:

2022 Toyota Camry

Mileage: 15000.0

2021 Honda Civic

Mileage: 28000.0Changing car1’s mileage doesn’t affect car2. They’re separate objects.

The this Keyword

Inside a method, this refers to the current object. It’s useful when parameter names match field names.

public class Person {

String name;

int age;

void setInfo(String name, int age) {

this.name = name; // this.name is the field, name is the parameter

this.age = age;

}

}Without this, the parameter shadows the field. The assignment name = name would do nothing useful. Using this.name clarifies that you mean the object’s field.

You can also use this for clarity even when there’s no naming conflict:

void displayInfo() {

System.out.println(this.name + " is " + this.age + " years old");

}Methods That Return Values

Methods can compute and return values based on an object’s state.

public class Rectangle {

double width;

double height;

double getArea() {

return width * height;

}

double getPerimeter() {

return 2 * (width + height);

}

boolean isSquare() {

return width == height;

}

}Using the class:

Rectangle rect = new Rectangle();

rect.width = 5;

rect.height = 3;

System.out.println("Area: " + rect.getArea()); // Area: 15.0

System.out.println("Perimeter: " + rect.getPerimeter()); // Perimeter: 16.0

System.out.println("Is square: " + rect.isSquare()); // Is square: falseMethods That Take Objects as Parameters

Methods can accept objects as parameters, enabling objects to interact.

public class Player {

String name;

int health;

int attackPower;

void attack(Player target) {

System.out.println(this.name + " attacks " + target.name);

target.health -= this.attackPower;

System.out.println(target.name + " health: " + target.health);

}

}Using the class:

Player hero = new Player();

hero.name = "Hero";

hero.health = 100;

hero.attackPower = 25;

Player enemy = new Player();

enemy.name = "Goblin";

enemy.health = 50;

enemy.attackPower = 10;

hero.attack(enemy);

enemy.attack(hero);Output:

Hero attacks Goblin

Goblin health: 25

Goblin attacks Hero

Hero health: 90Default Field Values

Fields get default values if you don’t assign anything:

- Numeric types: 0

- boolean: false

- Object references: null

public class Demo {

int number; // defaults to 0

boolean flag; // defaults to false

String text; // defaults to null

}Relying on defaults can be risky. Explicit initialization makes your intent clear.

Organizing Files

Each public class typically goes in its own file. For small programs, you can put multiple classes in one file if only one is public.

// File: Main.java

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Helper h = new Helper();

h.doSomething();

}

}

class Helper { // Not public, so it can be in the same file

void doSomething() {

System.out.println("Helping!");

}

}For larger projects, one class per file is standard practice. It makes code easier to find and maintain.

Practical Example: Bank Account

Here’s a more complete example modeling a bank account:

public class BankAccount {

String accountHolder;

String accountNumber;

double balance;

void deposit(double amount) {

if (amount > 0) {

balance += amount;

System.out.println("Deposited: $" + amount);

} else {

System.out.println("Invalid deposit amount");

}

}

void withdraw(double amount) {

if (amount > 0 && amount <= balance) {

balance -= amount;

System.out.println("Withdrew: $" + amount);

} else if (amount > balance) {

System.out.println("Insufficient funds");

} else {

System.out.println("Invalid withdrawal amount");

}

}

void transfer(BankAccount target, double amount) {

if (amount > 0 && amount <= balance) {

this.balance -= amount;

target.balance += amount;

System.out.println("Transferred $" + amount + " to " + target.accountHolder);

} else {

System.out.println("Transfer failed");

}

}

void printStatement() {

System.out.println("Account: " + accountNumber);

System.out.println("Holder: " + accountHolder);

System.out.println("Balance: $" + balance);

}

}Using the BankAccount class:

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

BankAccount alice = new BankAccount();

alice.accountHolder = "Alice Smith";

alice.accountNumber = "1001";

alice.balance = 1000;

BankAccount bob = new BankAccount();

bob.accountHolder = "Bob Jones";

bob.accountNumber = "1002";

bob.balance = 500;

System.out.println("=== Initial State ===");

alice.printStatement();

System.out.println();

bob.printStatement();

System.out.println("\n=== Transactions ===");

alice.deposit(200);

alice.withdraw(50);

alice.transfer(bob, 300);

System.out.println("\n=== Final State ===");

alice.printStatement();

System.out.println();

bob.printStatement();

}

}Output:

=== Initial State ===

Account: 1001

Holder: Alice Smith

Balance: $1000.0

Account: 1002

Holder: Bob Jones

Balance: $500.0

=== Transactions ===

Deposited: $200.0

Withdrew: $50.0

Transferred $300.0 to Bob Jones

=== Final State ===

Account: 1001

Holder: Alice Smith

Balance: $850.0

Account: 1002

Holder: Bob Jones

Balance: $800.0Common Mistakes

Forgetting to create an object. You can’t call methods on a class directly (unless they’re static). You need an instance.

// Wrong

Car.displayInfo(); // Error: non-static method

// Right

Car myCar = new Car();

myCar.displayInfo();Null pointer exceptions. If you declare a variable but don’t create an object, it’s null. Calling methods on null crashes.

Car myCar; // Declared but not initialized (null)

myCar.drive(10); // NullPointerException!Confusing class and object. The class is the blueprint. The object is the instance. You define fields in the class. You set values on objects.

Filename mismatch. A public class must be in a file with the exact same name. public class Car must be in Car.java.

What’s Next

Setting fields directly after creating an object is tedious and error-prone. Constructors solve this problem. The next tutorial covers constructors, which let you initialize objects with proper values at creation time.

Related: Introduction to Object-Oriented Programming | Java Constructors

Sources

- Oracle. “Classes.” The Java Tutorials. docs.oracle.com

- Oracle. “Objects.” The Java Tutorials. docs.oracle.com